Last February, University of Central Florida student Nicholas Lutz posted on Twitter photos of an apology letter written by his ex-girlfriend marked up, in red ink, with comments as if it were an essay for a class.

Lutz’s tweet, in which he graded the letter a D-minus, went viral, garnering (by publication time) about 121,000 retweets and almost three times as many likes. It was picked up by national media outlets like ABC News and the Washington Post. Even international sources, like the Swiss newspaper 20 Minuten, covered the story.

But then the post became more trouble than Lutz expected. On June 26, following a criminal complaint filed by his ex-girlfriend to the Volusia County Sheriff’s Office, Lutz was suspended for two semesters, initially for violating the “violation of local, state, and/or federal laws” provision of UCF’s Golden Rule. He also had to write a presentation and an essay about the incident and be paired with a university-appointed mentor for the rest of his academic career at UCF.

Lutz and his attorney Jacob Stuart appealed, citing that there was no evidence that the case was worth prosecuting and Lutz was therefore not in violation of any laws. In fact, the appeal letter said, the state attorney’s office did not find the case “suitable for prosecution” and the matter was dropped.

UCF’s charges against Lutz then changed to “harmful behavior” and “disruptive conduct.” The charges and the sanctions were later dropped and, as of July 20, dismissed.

As the story developed, Lutz became a hero for most and a jerk for some, although a majority on both sides seem to agree: he had every right to post those photos.

When Knight News published the story on Facebook, that majority of commenters praised UCF’s decision to drop the sanctions and Lutz for standing up for free speech.

“Free speech, period,” one user posted. “Stop with the constant whining.”

Another user expanded on the free speech point.

“The real question is who at UCF is so out of touch with reality that they thought suspension was an appropriate response to something that’s ultimately none of their business and had enough authority to push the suspension all the way through,” he commented.

A minority of commenters, however, denounced the tweet that began the controversy.

“Ultimately the suspension couldn’t hold up, but so proud of UCF for trying to make an example out of this asshole,” commented Al Anzola. He debated with others about the decision, saying that Lutz’s ex-girlfriend “just endured an amount of public shame and embarrassment you’ll probably never have to go through.”

“Even if the suspension wasn’t upheld, UCF is making a bold statement that it won’t tolerate stupid bullshit like this from men on college campuses who refuse to grow up,” he wrote.

Anzola’s comment was probably the most outspoken one in the article’s comment section, but it does beg the question: when can universities police online speech?

After speaking with a number of experts and reviewing relevant case law, the answer is not as black or white as one might think. Kimberly Lau, a partner with the New York-based law firm Warshaw Burstein who specializes in college disciplinary matters, said that UCF would have needed to meet a certain standard to punish “off-campus speech, even if the speech hurts someone’s feelings by pointing out errors in grammar in the letter.”

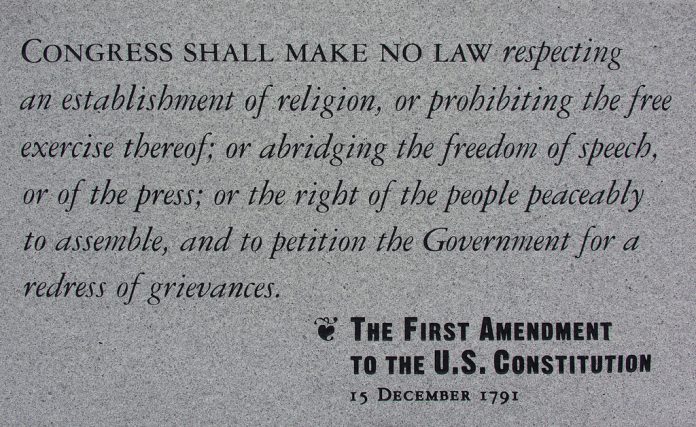

“From a First Amendment standpoint, a public university cannot punish a student’s speech unless it can show the speech ‘materially and substantially interfere[s]’ with the operation of the school,” she wrote in an e-mail to Knight News.

She was citing the 1969 Supreme Court case Tinker v. Des Moines, which famously ruled that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech at the schoolhouse gate.” That case involved high school students who wore black armbands to school to protest the Vietnam War.

Since then, however, the Supreme Court has given latitude to high school administrators to police their students’ speech. Much of that power comes from the 1988 Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier case in which a principal decided to censor two student newspaper articles dealing with teenage pregnancy and divorce. The Court ruled in favor of the school, arguing that administrators can censor speech if it is “inconsistent with its basic educational mission.”

With the ubiquity of social media, the power to censor has moved online. As the principal of an Arizona high school said last month to PBS NewsHour, “when something’s posted on social media and it’s being talked about on campus and it disrupts learning,” administrators can then decide what steps they can take to address it.

But in the university arena, policing speech between two individuals is trickier. After all, the majority in the Hazelwood case clarified that their decision did not apply to higher education.

“The Supreme Court’s precedent doesn’t deal with this area of education,” said Lyrissa Lidsky, a first amendment scholar and dean of the University of Missouri’s law school. “They deal with high school students, not college students. Their ability to police the speech of high school students is higher than for college students, like the ability to police high school students is lower than for elementary school students.”

While universities can police speech that disrupts its educational mission—like, for example, a student threatening another in class—it is another scenario entirely when that speech is made off-campus.

In Lutz’s case, UCF faced an additional problem—his ex-girlfriend is in high school. While UCF mentioned in a letter to Lutz that she “plans to attend UCF in the future,” Lidsky argues that they still did not have the right to suspend him in the first place.

“The first problem is the First Amendment and the student has a right to express his ideas and opinion even if that’s offensive,” she said. “The other problem is this was a break-up and the university doesn’t have the jurisdiction to be the Break-up Police, especially when one of the parties to the break-up is not even a student at the university.”

“That’s not the government’s job. That’s the job of social norms.”

Yet there is a debate that has become more and more relevant when it comes to social media speech, namely the blurring line between what is considered on campus and off campus.

“It used to be that it wasn’t that hard to say, ‘oh, on campus speech is one thing and what you say at a bar off campus or what you say in your home off campus is another’—there was a clear dividing line,” Lidsky said. Universities have the obligation to prevent harassment while protecting their students’ right to free speech, but “knowing where the line is between those two things can be difficult in this era.”

Cases related to social media speech are far from new. In 2007, Connecticut high school student Avery Doninger was banned from student government after posting comments criticizing school administrators over a canceled battle of the bands event. The district court and US Court of Appeals upheld the ban, saying the comments, which included a call on readers to complain to the school, was disruptive. The Supreme Court denied a petition to hear the case.

And these cases have been going on even before then, and since (check out this list from the National Coalition Against Censorship for more).

There are indications that the courts are beginning to deal with that line when it comes to universities, with mixed results.

In Keefe v. Adams, a Minnesota nursing student was removed from his program for “unprofessional” Facebook posts, including one where he said he would take an electric pencil sharpener to class and “give someone a hemopneumothorax,” an internal vessel rupture in the chest that can be caused by blunt trauma. The 8th US Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the school, ruling that “[m]any courts have upheld enforcement of academic requirements of professionalism and fitness” for licensed medical professionals. It did, however, controversially base the ruling on Hazelwood, which was not intended to apply on the collegiate level.

The 2015 case of Yeasin v. University of Kansas, however, bares an eerie resemblance to the Lutz case. Similarly, Navid Yeasin posted tweets about his ex-girlfriend which were considered derogatory and offensive, even though her name was never used. He was later expelled based on the university’s student code prohibiting policy violations that occur “on university premises or at university-sponsored or -supervised events.

The obvious difference is that the tweets not only allegedly violated UK’s conduct regulations, but also a no-contact order. And the criminal complaint filed against him differed in that he was charged with, among other things, criminal restraint.

Still, the Kansas Court of Appeals sided against the university, arguing that the language of the student code did not apply in this case. While questions regarding the university’s Title IX obligations and whether the tweets were protected free speech were mentioned in the case, neither were addressed because of the wording of UK’s student conduct policy.

“While the ruling vindicated Yeasin’s right to be free from punishment for his off-campus speech, it was based more on an interpretation of the college’s own rules than the First Amendment, so the case’s value as precedent for future constitutional challenges is uncertain,” the Student Press Law Center said at the time.

This question will likely be addressed in the future as social media continues to blur the line between on- and off-campus speech and as online speech can bring the offline consequences into the classroom.

“Have people said nasty things to each other in break-ups? Yes, since time immemorial, but now we have a permanent record online of the nasty things people say to each other in more cases than we used to and that creates some issues. A university here thought that is something that should be addressed,” Lidsky, the first amendment scholar, said of the Lutz case.

The implications go beyond what can happen to a student who posts a letter from their ex on social media. While online communication is becoming more widespread and almost essential to campus life, the courts are barely catching up.

“If one student is terrorizing another on social media such that they’re deprived of the ability to feel safe on campus, that would be a different scenario,” Lidsky said.

But until that scenario is brought to the courts, providing a clear answer to the question is still up in the air.