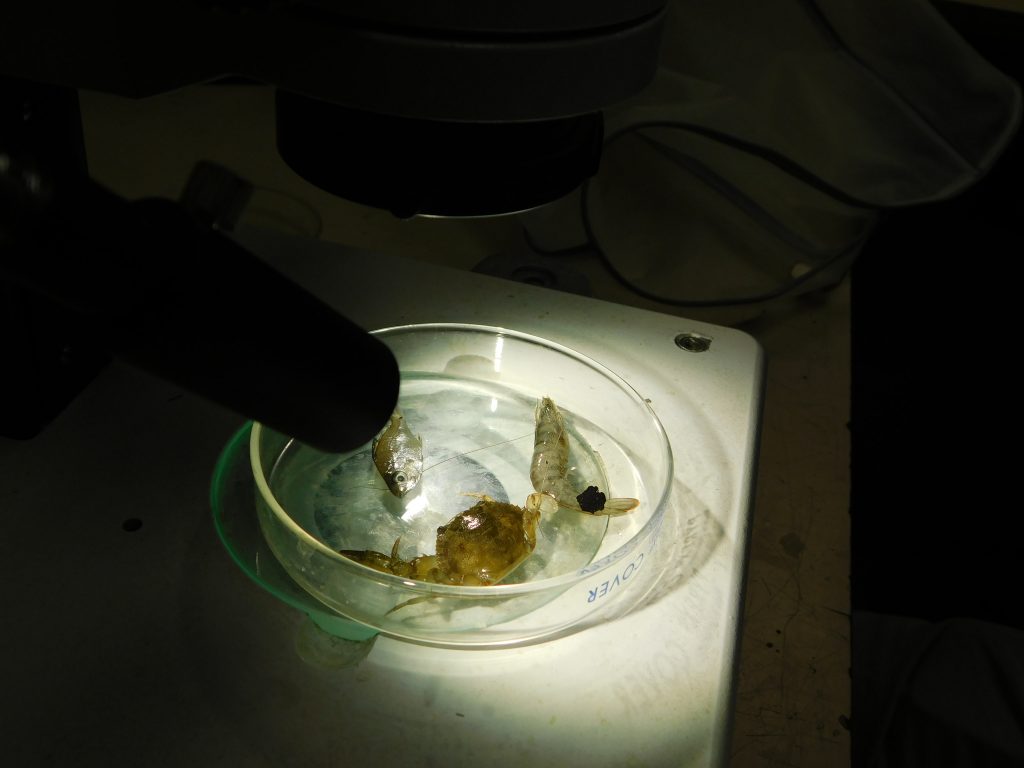

On a late September afternoon Adam Searles was going through his bucket of shrimp in a conservation lab to examine his aquatic findings. This time Searles was examining the gills of a little shrimp.

Adam Searles, a recent UCF alumnus has taken his biology studies from Orlando to the Atlantic coast. Searles works on behalf of Florida’s environment in the most diverse estuary in North America at the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission in Melbourne.

Searles said he was always fascinated with marine life and knew from an early age studying wildlife would be his career.

“Research gives you a sneak peek into a world that not many people get to see,” Searles said. “But you’re also doing good for the habitat that you’re admiring.”

The Indian River Lagoon is home to over 14 federally threatened or endangered species and 45 more species listed by the state as threatened, endangered, special concern or commercially exploited, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Wildlife populations are declining in the Indian River Lagoon due to the environmental impacts of rapid population growth. This is the same wildlife that sustain a healthy ecosystem and ultimately society.

“Our fish quality is a reflection of what may happen to us. So, we must work for what we want for our lives,” said Richard Paperno, a monitor adviser at FWC who devoted his life to conservation for over 30 years and trained Searles.

As a part of Searles’ job he monitors aquatic species of the lagoon and collects samples to observe diseases and population declines. Searles said his work has been gratifying to understand the interconnected factors that allow ecosystems to flourish.

“Civilization can’t live without properly functioning ecosystems,” Searles said. “Because if you take out the ecosystem, it’s like a house of cards, the whole thing falls.”

Species stability is not only important for wildlife but directly to people as well, Searles said.

When Searles is researching different aquatic species he’ll typically collect a sample and examine their gills and other body parts through a microscope. He searches to find anything peculiar, such as the species growing to a smaller size, or discoloration.

Searles emphasized the importance of paying attention to species at the lower levels of the food chain. These lower-level species matter indirectly because their stability has an ecological ripple effect. That’s why the FWC uses ecosystem-based science, because it considers all species, Searles said. A species may appear insignificant to most people but provide food to the game fish which directly effects fisheries and subsequently the economy.

Searles said it’s been a humbling experience to work in nature and understand wildlife more.

Another active member of the UCF community is Melinda Donnelly, a UCF biology postdoctoral fellow who has also devoted her work to conservation on the Indian River Lagoon. She has recently been focusing on the social dimensions of the ecology of the lagoon.

Donnelly is researching the lagoon through the experiences of local people who live there, on how the lagoon has changed over the years. Donnelly said what she hears most often from people is how congested the surrounding area of the Indian River Lagoon has become. People typically complain about the overcrowding because it diminishes the number of vital flood control wetlands of the lagoon, she said.

“The wetlands are definitely one of our most underappreciated ecological systems,” Donnelly said. “We realized that we rely on them for so many ecosystem services. Now we know wetlands support everything from cleaning up all the storm water to supporting local fisheries.”

The diseases fish can get from the diminished water quality due to pollution effects the overall trajectory of the entire aquatic population, Searles said.

Preservation of these important ecosystems has become crucial. Donnelly spoke about major threats, and how people are influencing ecosystem declines in more ways than population increase.

“Our water systems are affected by the use of the fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides which eventually ends up in our waterways and into the ecosystems,” Donnelly said. “What are you putting in your yard and are you contributing to a much larger problem?”

Despite damages that have been done to the ecosystem, Donnelly said it isn’t the end. She said the process of spreading awareness about the ramifications begins and continues with more initiatives, like reducing the use of plastic and proper disposal of fertilizers to prevent degradation of the ecosystem.

“Wetlands are very resilient and if you give them the opportunity to recover, most of the time they will,” Donnelly said. “So, just because wetland coverage has been altered in the past doesn’t mean it’s a lost cause. It’s definitely worth trying to get back to its natural function.”